Until Everyone Is Free

Stoneface Bombaa, whose government name is Brian Otieno, was born and raised in Mathare, which sits in a river valley in Nairobi, its bare rock cliffs a nod to its history as a quarry in colonial days. It doesn’t look too different now than it did then; only the corrugated metal roofs have grown in number. Hemmed in on all sides by police stations and barracks, Mathare is still surveilled in much the same way it was under British colonization, treated more as a reservoir for cheap labor than a constituency of citizens.

As a member of Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC), a grassroots organization that documents police killings and other extrajudicial injustices in Mathare, Nairobi, Stoneface is part of a working-class movement that resists everyday violence in the city’s informal settlements. Through his work with MSJC, Stoneface has come to understand that cholera, teenage pregnancies, frequent fires, trash heaps, and busted, decades-old water pipes—the very problems that attract NGOs and charities to Mathare like fruit flies—are all symptoms of capitalism working as it should. He’s stopped calling his home a “slum” and started calling it an “exploited community.” His work has now expanded into political education, as he volunteers to teach kids and, hopefully, give them the political consciousness he only got as an adult.

I first met Stoneface in June 2020, while I was reporting a story about police violence in Nairobi during the pandemic. Stoneface explained to me that a police bullet may end a life in an instant, but it is the environment—the symptoms of exploitation, the undignified living conditions—that denies the people of Mathare humanity. Worse, he told me, was that the oppressed don’t know their enemy, “so that the moment a politician gives them something, they clap and say you have done something.”

Stoneface showed me some faded bruises on his chest and arms from being beat up. A few weeks prior, he was walking home along Mau Mau Road, the main artery running through Mathare, when he passed by a baze—a gathering spot for the kinds of young men that police call “thugs” and gun down—called Comrades Self-Help Group. That day, a larger-than-usual group was celebrating with a subwoofer, so Stoneface asked them what was up. One told him that an electioneering politician had donated a set of jerry cans and a mkokoteni, a hand-pulled rickshaw for fetching water.

They were celebrating their own subjugation, Stoneface thought, happy to receive crumbs and confuse oppressor for savior. He reprimanded them: instead of celebrating when you get these, he said, you should have demanded the politician explain why in 2020 Mathare still doesn’t have water.

Stoneface wanted them to understand why there are two Nairobis: one with publicly piped water and well-paved roads, where the Constitution applies, and another where water is fetched and sold at prices inflated by water cartels. Had they been taught their history, they might know that they were standing on the hallowed ground of Kenyan freedom fighters, or that Mau Mau Road was named after the eponymous militant anticolonial insurgency whose War Council headquarters was located in Mathare. Maybe if they knew their history, they would see themselves as foot soldiers on a journey for liberation that began more than 70 years ago.

The Comrades found Stoneface’s lecture sanctimonious, and things turned violent quickly. “People like you are always resisting development,” he recalls them telling him. If you don’t know your history, you don’t know where you’re headed, he mused as he recalled the story. History is a passage from one generation to another generation; we inherit our history.

A true history of resistance would include how the very freedom fighters to whom Kenya owes its independence were betrayed by post-independence elites—but this is not the history Stoneface learned in school. As a child, he saw statues of Mau Mau fighters and Jomo Kenyatta in the city and assumed that Kenya owed its independence to both, equally. Only later, outside of the classroom, did he learn that the former are still waiting to get their land back, while the latter became the president in 1963 and the patriarch of the most landed family in Kenya.

After our interview, as Stoneface and I walked to catch a cab, we lamented the extent to which histories of resistance in Kenya had been sanitized. There are only two libraries in Mathare, and the books they stock are mostly foreign donations. Libraries, universities, and other public stewards of history were heavily defunded during structural readjustment in the 1980s and ’90s and often sit derelict. The books that are available are usually in “deep English” or formal, standardized Kiswahili, not the language they think in—Sheng, an ever-evolving urban patois, the lingua franca of Kenya’s informal settlements.

Stoneface had an idea: we should work on something together—aside from the article I was writing—that would bring history to the people. Perhaps we could write a booklet or set up a pop-up exhibition at MSJC. But was that much different from putting history behind glass? What if we not only made history accessible, but wrote it from scratch, with an agenda of political consciousness? What if we retold history in a way that allowed it to be wielded as a political tool, to radicalize the oppressed and decolonize the mind?

We decided to create a serialized podcast where we could be as overtly political as we wanted. It would be available for free on all streaming platforms and we could host listening sessions at social justice centers—bringing the history to people, where they already are. Although the podcast medium is relatively new in Kenya, our work would be only the most recent iteration of a long lineage of gathering around stories of freedom. By using the tools of audio production and the language of the youth, we hoped to reach people with a story that could not have been made for anyone but them.

We decided to call the podcast Until Everyone Is Free.

![]()

In 1984, a young British-Kenyan librarian at the University of Nairobi named Shiraz Durrani was writing a script for an ostensibly harmless cultural play about Kinjeketile Ngwale and the Maji Maji Rebellion, a Tanganyikan anticolonial legend. But he subtly adjusted the script: “We made it more relevant to Kenya, and more revolutionary.” Durrani was part of the December Twelfth Movement (DTM), an underground organization of intellectuals and workers that aimed to overturn the dictatorial regime of Kenya’s second President Daniel arap Moi.

After suppressing a coup attempt in 1982, Moi seized the opportunity to ratchet up surveillance, suppression, and persecution. During this time, Special Branch police officers routinely visited university libraries to track who had borrowed Marxist literature. To utter the word “socialism”—or mention anyone associated with it—in a bus or a restaurant was to risk being overheard by ubiquitous informants and taken in for interrogation.

By then, many political dissidents had already fled the country; the onslaught of attacks on leftist and pro-democracy organizing had been years in the making. In 1977, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii worked with villagers at the Kamiriithu Community and Cultural Center in Limuru to produce a play in Gĩkũyũ called Ngaahika Ndenda (I Will Marry When I Want). It was this play—written in a language and idiom people understood, performed in an open-air theater—and not his scathing English-language novel Petals of Blood, published that same year, which got him and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii detained in a maximum-security prison for a year without trial, after which both fled into exile.

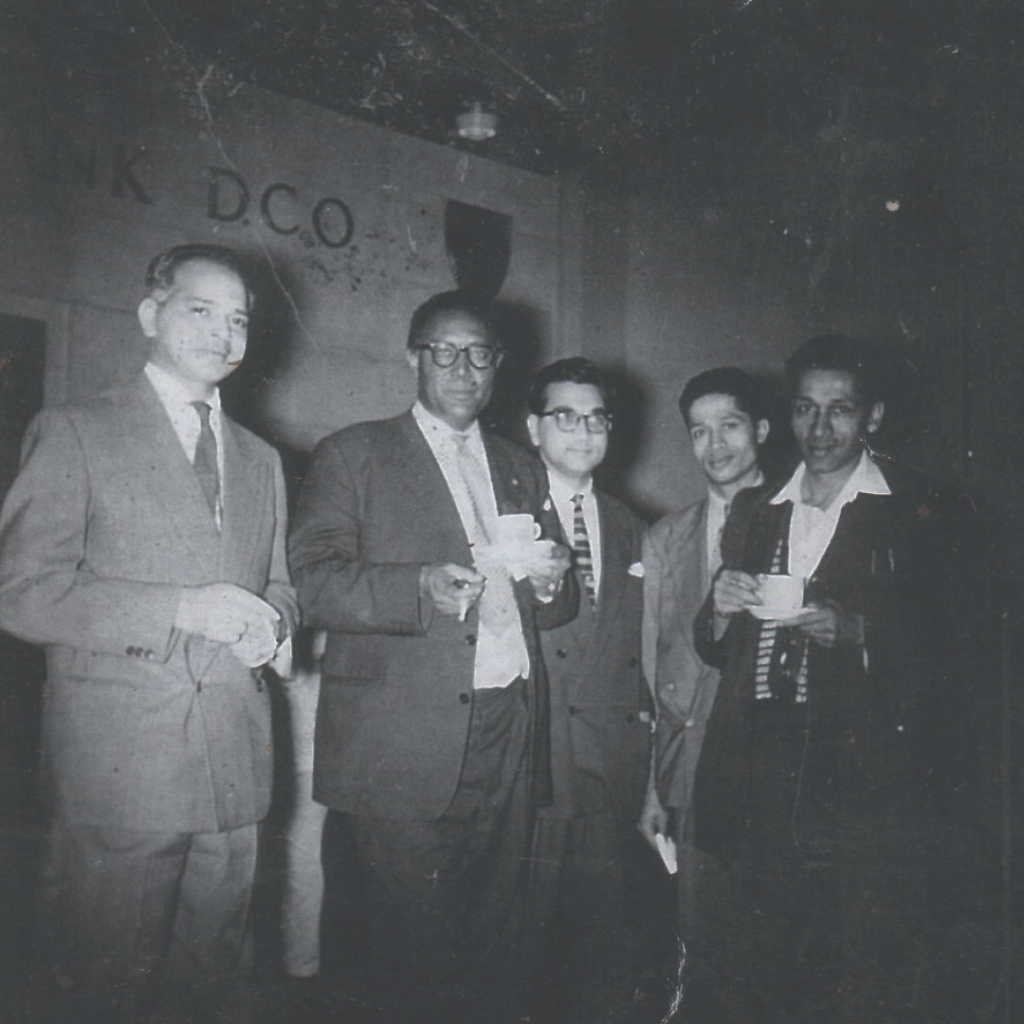

When Durrani was conducting research for his book, Never Be Silent, he happened across an old text from 1966 called Pio Gama Pinto: Independent Kenya’s First Martyr. Durrani had heard of Pinto and knew the Goan-Kenyan member of parliament was assassinated at the age of 38. But Durrani was shocked to read that Pinto was a part of the same ideological lineage as himself. Pinto was born in Nairobi in 1927 to a bourgeois Goan family and sent to India for schooling, but his political education came from the Indian anticolonial struggle. By the age of 17, he had helped organize a workers’ strike in Mumbai, and by his early 20s, his organizing with Goan freedom fighters made him a wanted man by both the British and Portuguese. After a warrant for his arrest was issued In 1949, Pinto fled back to Kenya.

As Durrani flipped through that book, he marveled at how a murdered freedom fighter flew beneath the radar of public discourse for decades—yet, as a DTM member, he knew why this leftist history had been erased. After the 1982 coup attempt, much of DTM leadership had been detained, exiled, or disappeared. “At that time, it became clear that the organization was facing a crisis,” Durrani tells me over Zoom. “Although there were lots of cells and organizations all over, there were no connecting links.” Durrani decided, “perhaps foolishly,” to send out a signal to other members that the DTM was still alive. In 1984, he did this by publishing an article on Pinto, drawing heavily from Patel’s book, in The Standard.

Durrani was indeed visited by the Special Branch for questioning and ultimately forced to seek political asylum in London, where he remains to this day. There he continued to collect primary sources on Pinto, an endeavor that would stretch across four decades, culminating in the 2018 publication of a book called Pio Gama Pinto: Kenya’s Unsung Martyr. The book has a bright yellow cover, and that was what caught the eye, in Mathare in 2020, of a young man called Stoneface.

Like young Durrani, Stoneface recalled having read a short paragraph about Pinto in a school textbook. But, while Durrani knew why Pinto had been censored in the two decades following his assassination, Stoneface realized that in the 21st century this information didn’t have to be censored anymore. No one knew about him, and no one seemed to care. Stoneface skimmed the book and was shocked to learn that, at a time when most Indian-Kenyans were more invested in economic stability than African nationalism, Pio Gama Pinto plunged himself into the trenches of the Kenyan anti-colonial struggle.

Unlike other African colonies, Kenya was a settler colony, a “white man’s country” premised on mass land annexation and alienation. From 1952 to 1960, the British colonial administration declared a state of emergency under martial law, setting up concentration camps and open-air detention centers to root out resistance fighters. With the help of a loyalist Home Guard, Mau Mau suspects were rounded up, screened, interrogated, tortured, and killed.

What Stoneface found remarkable was that, even as Kenya’s struggle for independence became so multi-pronged, somehow, across these various modes of resistance, Pinto seemed to be everywhere behind the scenes. He was there helping elders type and file their legal land claims; he was there organizing laborers in Nairobi and striking dock workers in Mombasa; he was there manually printing radical newspapers using a cyclostyle at his day-job office; he was there connecting freedom fighters in Kenya to others in Africa, and, when it came time for war, he was there inside the Mau Mau, not just financing activities but actively routing weapons from Asia to fighters via Mathare.

As Stoneface kept reading, he realized that “Pio Gama Pinto was also fighting for the same things we are fighting for in Mathare—land, freedom.” Our podcast theme became clear: we would resurface the life and work of Pio Gama Pinto, and in doing so, explain the mystery of Kenya’s incomplete decolonization. How did the country of Kenya become free without the liberation of its people?

We initially scripted six episodes, each of which captured a role Pinto played in the independence struggle: Mau Mau ally, land justice advocate, radical journalist, trade unionist, political mastermind and, finally, martyr. What emerged was a story of betrayal: how freedom fighters to whom Kenya owes its independence were erased, their politics sanitized.

![]()

Stoneface and I set out to do research—I in the books and he on the ground. We were joined by Felix Omondi, a poet, self-proclaimed “hood communist,” and community archivist also born and raised in Mathare. Felix and Stoneface would conduct interviews, discussing topics like wage slavery and unionization with domestic workers and bartenders. When we wanted to explore a complex topic like land alienation, we invited a musician named Madolla to put it to song. I wrote the scripts for Season 1 in English, and they were translated by Felix, Wyban Kanyi, and an organization called Go Sheng which, in addition to translation, documents the ever-evolving patois.

Sheng is central to the podcast, in part because of accessibility. “There’s a difference when you are speaking about imperialism in English, the way we are used to hearing smart people speaking about it on TV in English or Swahili,” says Felix. “But what does imperialism mean in Sheng, what does colonization mean in Sheng?” If Until Everyone Is Free were in English or even Swahili, the podcast would have been different, not least because in Sheng Stoneface and Felix speak in the first person plural—our communities, our labor, our Mathare.

In the episode about Pinto’s internationalist organizing, Stoneface and Felix discuss the collaboration between Pinto and Malcolm X in the 1960s. Stoneface quotes Huey Newton, a Black Panther Party founder, in Sheng:

The police in our community couldn’t possibly be there to protect our property because we own no property. They couldn’t possibly be there to see that we receive due process of law for the simple reason that the police themselves deny us due process of law. And so it is very apparent that the police are only in our community not for our security but for the security of the business owners in our community, and so to see that the status quo is kept intact.

Newton could have been speaking about Mathare—and, translated into Sheng, in a way he was. The power of this quote, spoken and discussed in the shared language of exploited, working-class communities in Nairobi who experience the same violent policing that Black Americans do, for the same structural reasons, demonstrated the power of speaking in an overtly political register, in the language of the people.

At a listening session at the Ruaraka Social Justice Centre in Mathare, Stoneface and Felix saw listeners perk up when they realized this podcast was actually in Sheng. “It was like a one-on-one conversation, Pio Gama Pinto speaking to them in the language they understand, compared to […] getting the books in deep English and people not understanding it,” Stoneface says. One young man, from a family that had been in Mathare for generations, realized that his grandfather’s stories about guns moving through Mathare, which he had assumed were made up, were not only true, but part of a revolution he had not been taught in school.

In late 2020, after we had finished producing the first full episode, Stoneface invited a couple of members from the Comrades baze—the ones who didn’t beat him up—to join for a listening session. They all gathered under the shade of some young trees in a school compound garden. Stoneface played them the hour-long episode about the Mau Mau. When it ended, they were quiet. Finally, one said, “Wow, this is true.” Stoneface assumes that they must have passed some message to the rest of the group, because the next time he found himself along the bend of that road by the baze, the men who beat him up called out to him—and apologized.

“They [admitted] they didn’t really know what they were doing,” Stoneface recalls. For the first time, they saw the system, and not the symptoms. They were victims of a sanitized history, but when given the knowledge, it all made sense.

“As I always say, ‘I liberate, but I’m not a liberator,’” Stoneface says. “People liberate themselves.”

![]()

April Zhu is a freelance journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya. She is an editor at Guernica Magazine and a 2023 Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow.