Not Like Us

Joe Budden sank into a white couch, crossing his legs and exposing his black leather slide sandals. He was in casual summer mode in a white T-shirt, black shorts, and a trucker hat by designer Steven Othello emblazoned with the phrase, “Buy More Flowers!” The microphone was positioned just under his chin, a full salt-and-pepper beard showing his 43 years. He kept his sunglasses on despite being indoors. The topic of the day was why the namesake host of “The Joe Budden Podcast” was being credited by media outlets like Billboard, Vibe, and Complex for lighting the spark that would eventually take down Drake.

Kendrick Lamar served Drake the ultimate lyrical coup de grâce with the song “Not Like Us.” The diss record became a hit record, debuting at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in May, and then a pop culture moment, blared in sports arenas when Team USA beat Canada and name-checked by Vice President Kamala Harris while campaigning. But Joe Budden believed the unraveling began when he criticized Drake’s music back in 2016. “They set me up for the gusto again, but I walk into the trap ‘cause I’m Joe Budden,” he said, the pride palpable in his voice.

“The Joe Budden Podcast” is the premier hip-hop talk and music podcast. Hosted by rapper Joe Budden, who reached mainstream success with his 2003 self-titled album and underground credibility through a slew of mixtapes in the aughts and the rap group Slaughterhouse, the show began in 2015 under the name “I’ll Name This Podcast Later.” Since then, it has undergone revolving co-host changes, seemingly fueled by Budden’s brash and abrasive personality. In 2018, he signed an exclusive deal with Spotify and two years later left to launch The Joe Budden Network.

It takes a village to raise a child and, apparently, a village to dismantle the biggest rapper in the world. In the case of Drake, Budden believes he catalyzed his cohort. “It may sound narcissistic, but I don’t think any one man takes down Drake,” the rapper-turned broadcaster said on Twitter Spaces in June. In 2016, Budden called Drake’s album “Views” “fucking uninspired” on his podcast and the two then flung subliminal disses at each other, including Drake on his song “4pm in Calabasas.” During his “Summer Sixteen” tour in July 2016, Drake called out his foe by name, saying, “I should’ve brought Joe Budden up here and let him do ‘Pump It Up’ one time tonight. Pump, pump, pump it up. Fuck them n—-s, man.” Budden believes these ongoing conflicts with Drake inspired Pusha T to release his excoriating Drake diss, “The Song of Adidon,” in 2018, which in turn inspired Kendrick to confront the Canadian superstar. “I think I passed the baton to Push, I think Push passed the baton to Kendrick, and the job is done now. That’s how I feel in my head and my heart.”

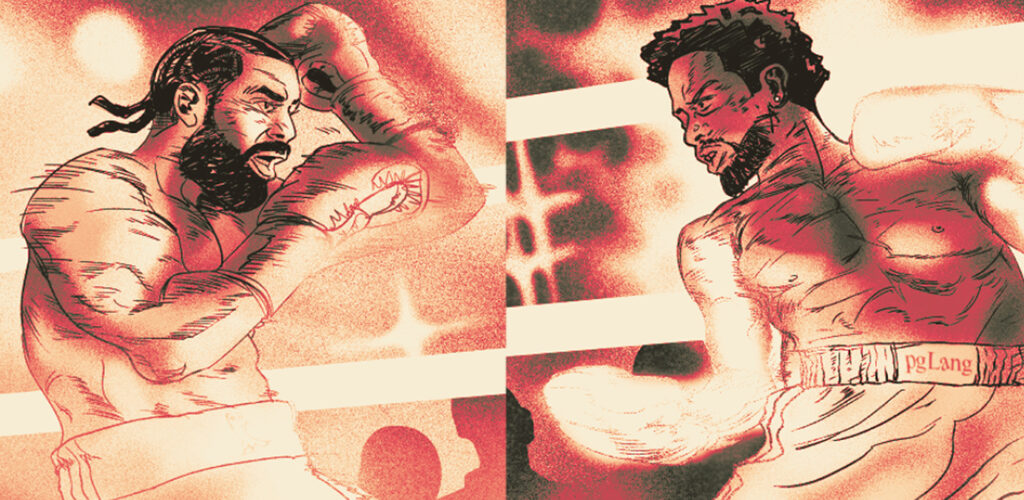

Competition has been intrinsic to hip-hop since its inception in the Bronx with dance crews, DJs, and emcees going back-and-forth and vying for top spot. But the rap battle between Drake and Kendrick Lamar marks the very first time in history that podcasters are part of the war.

The two behemoths traded barbs that ran the gamut of allegations, from using ghostwriters to domestic violence, pedophilia, and concealing secret children. Although tensions between the two had been simmering for at least a decade, originating on Kendrick’s verse on Big Sean’s “Control,” the battle began in March with the Compton rapper firing warning shots on Future and Metro Boomin’s “Like That.” After several back and forth diss tracks, things climaxed with Kendrick’s “Not Like Us” in May. This haymaker was the winner and not only ousted Drake from the top of hip-hop’s leaderboard but turned him into a cultural pariah.

On June 19, the holiday commemorating the ending of slavery in America known as Juneteenth, Kendrick Lamar performed “Not Like Us” six times during The Pop Out: Ken & Friends, a concert that brought out West Coast rap legends like Dr. Dre, YG, and DJ Mustard, and closed with warring gangs coming together. Los Angeles was united around Kendrick. LeBron James was seen dancing to “Not Like Us” and Megan Thee Stallion rapped the song onstage. The music video, which was released on July 4, amassed over 75 million views in two weeks and was the number one trending music video on YouTube. The song was shouted out by everyone from Argentina’s soccer team when they beat Canada, to the organist at a St. Louis Cardinals baseball game.

Historical hip-hop bouts—like those between Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. in the mid-1990s and, in the aughts, Jay-Z versus Nas and 50 Cent taking down Ja Rule—played out on the covers of Vibe, The Source and XXL, on MTV and BET, or on radio stations like New York City’s Hot 97. Now, podcasts are the battleground in discussing and dissecting every nuance. It wasn’t just Budden; Akademiks (“Off the Record with DJ Akademiks”) and Mal (“New Rory & Mal”) gave impassioned monologues about who was the victor and revealed insider information from within the rappers’ camps.

For the past five years, podcasts have emerged as influential platforms for criticism, storytelling, and cultural exchange in hip-hop. Instead of running to radio, which was traditionally king, superstar artists like Drake, Cardi B, and Nicki Minaj have opted to do interviews with podcasters, offering them sneak peeks at music. From intimate talks to raucous debates on new music and celebrity gossip, this form of media has increasingly usurped attention and relevance from heritage media. When Complex released its 2024 Hip Hop Media Power Ranking list in July 2024, it wasn’t a surprise that four of the top five spots were taken by podcasters (the one outlier being a YouTube streamer). And many of the personalities who were known from traditional media like Power 105.1’s Angie Martinez, Charlamagne Tha God of “The Breakfast Club,” and former XXL editor-in-chief Elliott Wilson recently launched their own respective podcasts to keep in step with the times. It was during this feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake that it became clear that podcasts were not only the leaders in reporting headlines—they were integral in creating them.

![]()

Hip-hop journalism emerged alongside the genre itself in the 1970s, evolving from grassroots zines and newsletters into a more defined form of music journalism in the ’80s. Hip-hop was initially documented through local newspapers and word-of-mouth around its origins in the South Bronx. But as the culture gained momentum, journalists began to document its significance, laying the groundwork for dedicated reporting. Early figures like Harry Allen and Davey D chronicled block parties, DJs, and rap battles at places like Adelphi University’s student radio station WBAU, the Washington Times, and KALX radio on the campus of UC Berkeley. Greg Tate is often credited as the godfather of hip-hop journalism for elevating hip-hop to the uppermost echelons of culture in The Village Voice. He likened Rakim to Miles Davis and wrote: “Rap keeps alive the lineage of jukejoint jive novelty records that began with the first recorded black music—so-called classic blues” in 1988.

Later, magazines like The Source, hip-hop’s bible, as well as Rap Pages, Vibe, and XXL were all cultural touchstones that chronicled hip-hop by those that loved it with in-depth interviews, reviews, and commentary on social issues. “In the beginning, it was kind of an even split. There was a small collection of journalists who had an existing friendship or relationship with the artist because they were all coming up together. There was a point in time where the goal was to get the story out,” said Kathy Iandoli, journalist, media coach, and author of “God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop.” Hip-hop journalists like dream hampton, Kevin Powell, and Hot 97 radio personality Angie Martinez rose as trusted names and secured coveted interviews with rappers like The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur, and Jay-Z because of their proximity to the artists. Kevin Powell, for instance, was summoned by Shakur from his jail cell for an exclusive interview with Vibe in 1995. “Once Pac and I started talking, it was just him and I,” Powell explained years later. “He just let it all out. He wanted to get all of this stuff off his chest.” hampton was so close to B.I.G. that she wanted him to be her daughter’s godfather. She captured fly-on-the-wall footage of the rapper that was repurposed into the 2024 vérité film “It Was All a Dream.”

So began a schism in hip-hop media between those covering it from the inside and those doing so from the outside. There was often a tacit (or explicit) expectation of being celebratory rather than critical. “For a hip-hop publication, it’s on us to be much more congratulatory and positive than a ‘mainstream outlet’ of outsiders covering this culture,” said Iandoli. So-called mainstream media was anything that was not made specifically for (or by) the hip-hop demographic; often it was for white audiences and made by white editors and journalists. As such, mainstream criticism was usually unwelcome. “If you had a critic critiquing the artist’s work, suddenly,” Iandoli said, “it was like, well, ‘Who do you think you are critiquing my art? Who are you to pick apart my music?’”

The digital age ushered in websites and blogs as new avenues for journalism. Due to the immediate nature of the internet, outlets like All Hip Hop, Okayplayer, NahRight, and Worldstar Hip Hop offered real-time news updates, audio and video, and interactive message boards and comment sections. Unlike their predecessors, journalists of the “blog era” were fans more than peers. Many were music nerds or socially awkward fanboys who happened to know how to use WordPress. They often gained notoriety through rogue tactics like leaking music without permission. The New Music Cartel (NMC) was a popular cadre of blogs—NahRight, 2DopeBoyz, OnSmash, YouHeardThatNew, Xclusives Zone, Miss Info, and DaJaz1—that became synonymous, as their name implied, with having music before everyone. “Nothing goes down unless we’re involved,” NahRight founder Ahsmi “Eskay” Rawlins said in May 2008. “No exclusives, no singles, no nothing. A freestyle is spit in the park, we want in. You guys [the music industry] got fat while everybody starved on the street. It’s our turn.”

Bloggers became tastemakers, and burgeoning rappers desperately wanted to get on their sites. Eskay told Complex that he helped launch the careers of Wiz Khalifa, Wale, and Drake. The latter’s success came from NahRight commenter-turned-blogger Nation, who was shouted out by Drake himself. Meanwhile, Meka of 2DopeBoyz believed he and partner Shake were among the first to spot talent in a young Kendrick Lamar.

![]()

“@joebudden you have failed at music,” Drake wrote underneath Akademik’s post on Instagram in October 2023. Drake was furious that Joe Budden had criticized his album, “For All The Dogs,” and taunted Budden for pivoting into podcasting in late 2023. “For any artist watching this just remember you are watching a failure give their opinion on his idea of a recipe for success…a quitter give their opinion on how to achieve longevity…”

Hip-hop podcasts are dominated by former rappers (Joe Budden, N.O.R.E., Math Hoffa, Cam’ron, and Ma$e) and industry outsiders (DJ Akademiks, Adam-22 of “No Jumper”) and as such, journalistic norms like professionalism, ethics, and fact-checking don’t apply. The hosts bring in their personal experiences, perspectives, and reactions. This approach adds a layer of authenticity and intimacy, allowing listeners to connect more deeply with the subject matter. Meanwhile, objectivity isn’t valued. Whoever gets the story first or reports it with the most drama and vigor gets the audience.

The distinction between a journalistic podcast host and a celebrity with an ax to grind got murkier as the battle continued. Hosts inserted themselves into the narrative, and Drake’s reputation, especially, was damaged as they shared negative experiences of the rapper and his October’s Very Own (OVO) crew. In May, during the apex of the feud, “Juan Epstein” hosts Peter Rosenberg and Cipha Sounds shared how Drake and his producer Noah “40” Shebib angrily turned on them when they were deemed disloyal. Since those hosts came from Hot 97, the preeminent hip-hop radio station, they had personal experiences with Drake who had once desperately needed them to validate his career. That same month, on “My Expert Opinion,” rapper-turned-podcaster Math Hoffa revealed that Drake had tried to steal a girl from him despite their professional camaraderie. Elliott Wilson of “Rap Radar,” who was friendly with Drake at one point, shared that the rapper had iced him out after faint criticism. “The BOY unfollowed me on IG,” he blasted on social media.

There was a time when airing such grievances would be considered unprofessional. Aside from the notion of “no snitching” in hip-hop, no journalist would dare burn bridges and lose access to a rap superstar, and the powers that be might kill any story that might inspire retaliation. Many outlets, mostly out of fear of legal reprisal or industry blackballing, would refrain from running allegations that could not stand up to fact-checking.

But podcasters operate by their own rules, and if they were never journalists to begin with, how would they even know the code of ethics? DJ EFN, creator and co-host of “Drink Champs,” underscored that he doesn’t see himself as a journalist. “I have a lot of respect for journalism. There’s ethics and criteria and things that you follow in journalism that we don’t do,” he said. “There’s deep digging, historical context. A rigor to it that I feel that we don’t adhere to.” On “Drink Champs,” rapper N.O.R.E. and EFN interview guests over hours fueled by alcohol and sometimes marijuana. It’s not meant to be incisive or an interrogation; instead, they bestow accolades and, as EFN explained, “give them their flowers.” “It’s a celebration of people and of the overall culture,” he said. “It’s very hard to get in that adversarial role with a guest when really that’s not the point of them sitting there.”

However, EFN thinks there is a problem with hip-hop podcasts operating without any type of conduct. “There’s so many talking heads and so much misinformation and so many people that monetize off that,” he said. “The biggest headline, the biggest clickbait, that you just never know what’s real.” In the case of Kendrick vs. Drake, the rap battle happened over the course of weeks, sometimes with disses being released within moments of each other, and there was no time to fact check. For instance, DJ Akademiks, considered to be a Drake surrogate, claimed that the rapper would release a new response after his finale, “The Heart Part 6”; that has yet to happen. Instead of this misinformation hurting the podcast, it’s become his calling card. “He represents what rap fans and rappers prioritize in hip-hop media right now; not necessarily truth or ethics, but entertainment with an anti-establishment streak. It’s not always great, if we’re being honest,” admitted Complex, while simultaneously crowning him the number one hip-hop media personality of 2024.

As long as the algorithm doesn’t differentiate between truth and fiction—and listeners don’t seem to care—podcasters are incentivized to say anything to keep the listenership up. “You can cherry pick whatever truth you want and create a whole narrative off of one or two truths,” said EFN about the trend of misinformation during the battle. “Even though everything else is a lie.”

In July, XXL ran a feature about how podcasts dominated the rap beef. “Things Done Changed,” the sub-header read, a reference to a song on The Notorious B.I.G.’s 1994 debut album. The irony wasn’t lost on anyone. The last standing print magazine from hip-hop media’s glory days was referencing a classic from a bygone era while announcing the changing of the guard. Meanwhile, DJ Akademiks was back in his chair, streaming live and proselytizing for Drake. “This is a confirmed thing from him to me,” he said to his fans. “Yo Ak, I’m back to giving everybody who loves me, what they love from me.” The news wasn’t news at all but the podcaster had to remind everybody he had the ear of the superstar. “That’s a direct quote. Ya’ll got it.”

![]()

Sowmya Krishnamurthy is a music journalist and author of the book “Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion.”