Hard Harry Rides Again

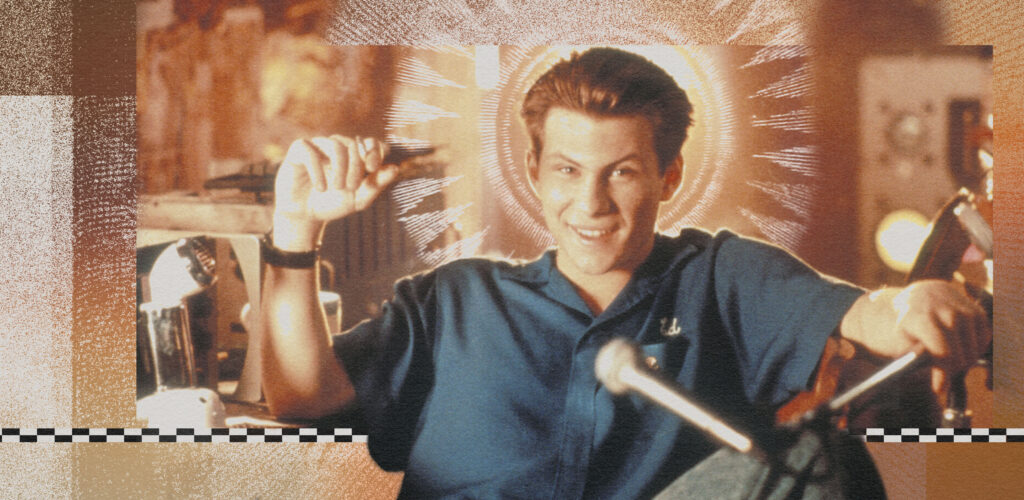

Earlier this summer, Criterion shared a collection themed around 1990s soundtracks or notable ’90s movies with particularly strong soundtrack albums, whether the retro compilation of “Grosse Pointe Blank,” the Britpop of “Trainspotting,” or the nascent rap-rock of “Judgment Night.” The teen drama “Pump Up the Volume,” in which a young Christian Slater plays a disaffected youth broadcasting a pirate radio program, was also among them, and as an August 22, 1990 release, was celebrating its 35th anniversary.

Technically, “Pump Up the Volume” fits in with other soundtrack movies. Slater’s character, Mark, whose nom de radio is Hard Harry, loves Leonard Cohen and punk rock, and the film’s accompanying album, featuring Concrete Blonde, Pixies, Sonic Youth, Soundgarden, and Bad Brains, went gold, making it a much bigger financial success than “Pump Up the Volume” itself. Watching it now, the movie doesn’t feel particularly plugged into ’90s alternative music culture. It’s a bit early for that. Temperamentally speaking, the younger characters largely feel like they’re impatiently waiting for Nirvana to materialize in the mainstream the following year, which tracks, given the movie was written and made between 1987 and 1989. Regardless, Hard Harry doesn’t talk much about the music he plays, often interrupting it with his own musings. A young dude? Interrupting? Musings? Yes, “Pump Up the Volume” now plays more like a movie about present-day podcasting.

Most current movies and TV shows that incorporate podcasting do so clumsily, inadvertently making the format seem as cheesily dated as flash mobs or planking. Despite a continued move to video, podcasting is such an uncinematic activity that you really have to go out of your way to show it, which usually means indulging in embarrassing signaling of the fictional podcast’s hipness or hilarity, especially if it’s the lead character’s main gig. For example, the Netflix movie “You People” takes time to bask in the glow of Jonah Hill and Sam Jay’s characters as they perform their supposedly funny podcast bits. Even less hilarious is the Netflix series “Nobody Wants This,” perhaps in part because it willingly admits that this stuff is sometimes just recorded on someone’s couch. This, of course, is why featuring podcasts feels particularly awkward, as the medium obviously connects to the lineage of terrestrial radio broadcasting, which is meant for the ears, not the eyes.

Old-fashioned terrestrial radio is the field that Mark invades as Hard Harry. He hijacks a local FM frequency to broadcast an anonymous solo show out of his parents’ basement, where he occasionally plays his favorite tunes but mostly vents about his loneliness (and horniness), jokes about his dead-end suburban existence (and horniness), and rants about his life as an antisocial high-schooler (and, well, you get the idea, though it’s difficult to convey just how much airtime Hard Harry dedicates to pretending to masturbate on mic). He also reads letters from listeners, mailed to an anonymous post office box, and calls them up to discuss their problems when they provide their phone numbers.

In other words, it’s a mélange of radio-show staples. Hard Harry’s antics feel especially predictive of podcasts, though, because of his place in the FM landscape of the 1990s, when there were still plenty of gainfully employed DJs and other radio personalities on the air. This was before Howard Stern went to satellite radio, after all. But American radio was about to undergo a significant change. The 1996 Telecommunications Act removed long-standing restrictions on the number of stations one company could own overall (previously capped at 40) or in a given market (previously capped at two each of AM and FM), and as the alternative-rock ’90s faded, radio became more homogenized, with some conglomerate-owned stations using the same canned patter across markets. Former signs of individual life between already similar playlists—such as, say, a DJ who might live in the town where they were broadcasting from—started to disappear.

Hard Harry anticipates this corporatization of the airwaves and, in response, inverts a familiar DJ dynamic. Instead of using his real name for generic patter, he anonymously bares his soul. The anonymity doesn’t particularly scan with podcasts, but a vision of broadcasting where philosophizing, ranting, or just doing bits takes precedence over generic “hosting” sure does. No wonder listeners have become more compelled by podcasts than by most of what lingers on the FM dial.

“Pump Up the Volume” depicts something even more contemporary: the parasocial relationships that can develop through mass communication. This isn’t unique to podcasts, but given their emergence after the rise of social media, podcasters have been especially well-positioned to build relationships with their listeners. The audience can feel like the object of their affection is speaking straight to them, whether through quick social posts or two-hour episodes. The movie also anticipates the flexibility of the podcast format, where self-released episodes don’t have to fit into a particular time slot; Hard Harry can pop on the air for 20 minutes or filibuster for multiple hours.

Crucially, the movie begins with Hard Harry already having attracted a following that’s far more devoted than any of Mark’s real-world relationships. Some of his fans feel like they know him, even though they often form incorrect assumptions based on his broadcasts. Fellow student Nora, played by Samantha Mathis, even goes so far as to lust after him. And while discovering the real identity of Hard Harry does seem to deepen her attraction, it’s still not as potent an aphrodisiac as his on-air persona. Yet the film becomes more serious — and even less music-focused — when its primary source of tension emerges: a listener-related tragedy, and the question of whether Hard Harry is partially responsible for it.

It’s telling that writer-director Allan Moyle didn’t have quite the same luck directing “Empire Records,” another ’90s soundtrack movie. Somewhat curiously — given its relative ubiquity and how its soundtrack reportedly sold four times as many copies as “Pump Up the Volume” — it isn’t canonized by the cinephile-beloved Criterion Channel streaming service. Perhaps this is because the collection was co-programmed by Yasi Salek, a podcasting kindred who hosts the popular show “Bandsplain.” It could also be because “Empire Records” is less attuned to how teenagers talk and think and has a greater desire for a feel-good wrap-up. “Pump Up the Volume,” by contrast, ends with a gratifying lack of full resolution, reassuring viewers that people will still feel alienated, authority figures will still feel threatened, and self-expression will still find a way to broadcast itself.

It’s surprising, too, that “Pump Up the Volume” hasn’t been earmarked for a podcast-era remake. A clever adaptation could certainly make some sharp observations more specific to podcasts and youth culture. But it might not be necessary; the movie, as it is, might already be a definitive statement of podcast idealism.

Jesse Hassenger is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn whose work appears in Paste, The A.V. Club, Polygon, Decider, and GQ, among others.